Contingency Theories and Adaptive Leadership

After studying this topic, you should be able to:

- Discuss how aspects of the situation can influence leader behavior and enhance or diminish the effects of leader behavior.

- Examine the key features of the early contingency theories of effective leadership

- Explain how to adapt leader behavior to the situation.

- Illustrate how to deal with demands, constraints, and role conflicts.

General Description of Contingency Theories

Contingency theories describe how aspects of the leadership situation can alter a leader’s influence and effectiveness.

The contingency theories of effective leadership have at least one predictor variable, at least one dependent variable, and one or more situational variables. The leadership attributes used as independent variables were usually described in terms of broad meta-categories (e.g., task and relations behavior). The dependent variable in most of the theories was subordinate satisfaction or performance, and in a few cases, it was group performance. Most of the situational variables were conditions the leader is not able to change in the short term, including:

- characteristics of the work (e.g., task structure, role interdependence),

- characteristics of subordinates (e.g., needs, values),

- characteristics of the leader (expertise, interpersonal stress), and

- characteristics of the leadership position (leader authority, formal policies).

Some contingency theories also include mediating variables (sometimes called “intervening variables”) to explain the influence of leader behavior and situational variables on performance outcomes. The mediators are usually subordinate characteristics that determine individual performance (e.g., role clarity, task skills, self-efficacy, task goals), but mediators can also include group-level characteristics that determine team performance (e.g., collective efficacy, cooperation, coordination of activities, resources).

Different Ways Situations Affect Leaders: Causal Effects of Situational Variables

1. Situation Directly Influences Leader Behavior.

A situational variable may directly influence a leader’s behavior but only indirectly influence the dependent variables. Aspects of the situation such as formal rules, policies, role expectations, and organizational values can encourage or constrain a leader’s behavior, and they are sometimes called demands and constraints. In addition to the direct effect of the situation on leader behavior, there may be an indirect effect on dependent variables. For example, a company establishes a new policy requiring sales managers

to provide bonuses to any sales representative with sales exceeding a minimum standard; sales

managers begin awarding bonuses and the performance and satisfaction of the sales representatives increases.

2. Situation Moderates Effects of Leader Behavior.

A situational variable is called an enhancer if it increases the effects of leader behavior on the dependent variable but does not directly influence the dependent variable. For example, providing coaching will have a stronger impact on subordinate performance when the leader has relevant expertise. This expertise enables the leader to provide better coaching, and subordinates are more likely to follow advice from a leader who is perceived to be an expert. An enhancer can indirectly influence leader behavior if a leader is more likely to use a behavior because it is perceived to be relevant and effective.

Situational moderator variables called a neutralizer when it decreases the effect of leader behaviour on the dependent variable or prevents any effect from occurring. For example, offering a pay increase to an employee for working extra days may fail if the employee is rich and does not need the money. Employee indifference to paying rewards is a neutralizer for this type of influence tactic.

3. Situation Directly Affects Outcomes or Mediators.

A situational variable can directly influence an outcome such as subordinate satisfaction or performance, or a mediating variable that is a determinant of the outcomes. When a situational variable can make a mediating variable or an outcome more favorable, it is sometimes called a “substitute” for leadership. An example is when subordinates have extensive prior training and experience. The need for clarifying and coaching by the leader is reduced because subordinates already know what to do and how to do it. A substitute can indirectly influence leader behavior if it becomes obvious to the leader that some types

of behavior are redundant and unnecessary.

A situational variable can also affect the relative importance of a mediating variable as a determinant of performance outcomes. For example, employee skill is a more important determinant of performance when the task is very complex and variable than when the task is simple and repetitive. Here again, the situational variable can indirectly influence leader behavior if it is obvious to the leader that some types of behavior are more relevant than others to improve performance for the leader’s team or work unit.

Contingency Theories

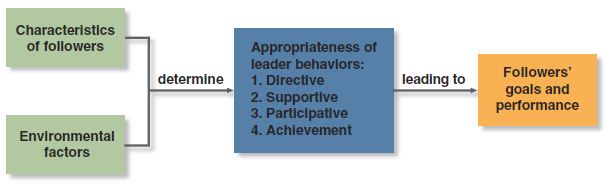

1. Path-Goal Theory by Robert House

Consistent with the expectancy theory of motivation, leaders can motivate subordinates by influencing their perceptions about the likely consequences of different levels of effort. Subordinates will perform better when they have clear and accurate role expectations, they perceive that a high level of effort is necessary to attain task objectives, they are optimistic that it is possible to achieve the task objectives, and they perceive that high performance will result in beneficial outcomes. The effect of a leader’s behavior is primarily to modify these perceptions and beliefs.

“The motivational function of the leader consists of increasing personal payoffs to subordinates for work-goal attainment and making the path to these payoffs easier to travel by clarifying it, reducing roadblocks and pitfalls, and increasing the opportunities for personal satisfaction en route.”

According to path-goal theory, the effect of leader behavior on subordinate satisfaction and effort depends on aspects of the situation, including task characteristics and subordinate characteristics. These situational moderator variables determine both the potential for increased subordinate motivation and the manner in which the leader must act to improve motivation. Situational variables also influence subordinate preferences for a particular pattern of leadership behavior, thereby influencing the impact of the leader on subordinate satisfaction.

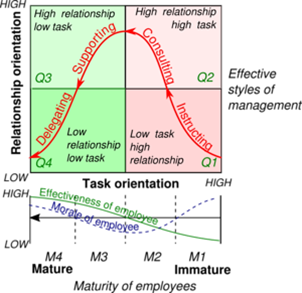

2. Situational Leadership Theory

Hersey and Blanchard (1977) proposed a contingency theory called Situational Leadership Theory. According to proponents of the situational approach to leadership, universally important traits and behaviors don’t exist. It specifies the appropriate type of leadership behavior for a subordinate in various situations. Behavior was defined in terms of the directive and supportive leadership, and a revised version of the theory also included decision procedures (Graef, 1997). The situational variable is subordinate maturity, which includes the person’s ability and confidence to do a task.

According to the theory, for a low-maturity subordinate the leader should use substantial task-oriented behavior such as defining roles, clarifying standards and procedures, directing the work, and monitoring progress. As subordinate maturity increases up to a moderate level, the leader can decrease the amount of task-oriented behavior and increase the amount of relations-oriented behavior (e.g., consult with the subordinate, provide more praise and attention). For high-maturity subordinates, the leader should use extensive delegation and only a limited amount of directive and supportive behavior. A high-maturity subordinate has the ability to do the work

without much direction or monitoring by the leader, and the confidence to work without much supportive behavior by the leader.

The primary focus of the theory is on short-term behavior, but over time the leader may be able to increase subordinate maturity with a developmental intervention that builds the person’s skills and confidence. How long it takes to increase subordinate maturity depends on the complexity of the task and the subordinate’s initial skill and confidence. It may take as little as a few days or as long as a few years to advance a subordinate from low to high maturity on a given task. Hersey and Blanchard recognized that subordinate maturity may also regress, requiring a flexible adjustment of the leader’s behavior. For example, after a personal tragedy such as the death of loved ones, a subordinate who was highly motivated may become apathetic. In this situation, the leader should increase supervision and use a developmental intervention designed to restore maturity to the former high level.

The situational variables include characteristics of the subordinates, task, and the organization that serve as substitutes by directly affecting the dependent variable and making the leader behavior redundant. The substitutes for instrumental leadership include a highly structured and repetitive task, extensive rules and standard procedures, and extensive prior training and experience for subordinates.

The substitutes for supportive leadership include a cohesive workgroup in which the members support each other and an intrinsically satisfying task that is not stressful. In a situation with many substitutes, the potential impact of leader behavior on subordinate motivation and satisfaction may be greatly reduced. For example, little direction is necessary when subordinates have extensive prior experience or training, and they already possess the skills and knowledge to know what to do and how to do it. Likewise, professionals who are internally motivated by their values, needs, and ethics do not need to be encouraged by the leader to do high-quality work.

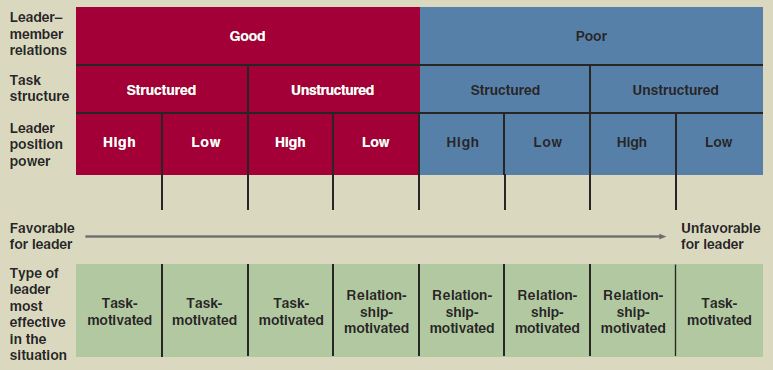

3. Fiedler’s Contingency Model

According to Fiedler’s contingency model of leadership effectiveness, effectiveness depends on two factors: the personal style of the leader and the degree to which the situation gives the leader power, control, and influence over the situation. The figure below illustrates the contingency model:

The upper half of the figure shows the situational analysis, and the lower half indicates the appropriate style. In the upper portion, three questions are used to analyze the situation:

- Are leader-member relations good or poor? (To what extent is the leader accepted and supported by group members?)

- Is the task structured or unstructured? (To what extent do group members know what their goals are and how to accomplish them?)

- Is the leader’s position power strong or weak (high or low)? (To what extent does the leader have the authority to reward and punish?)

These three sequential questions create a decision tree (from top to bottom in the figure) in which a situation is classified into one of eight categories. The lower the category number, the more favorable the situation is for the leader; the higher the number, the less favorable the situation. Fiedler originally called this variable “situational favorableness,” and later “situational control.” Situation 1 is the best: relations are good, task structure is high, and power is high. In the least favorable situation (8), in which the leader has very little situational control, relations are poor, tasks lack structure, and the leader’s power is weak.

Different situations dictate different leadership styles. Fiedler measured leadership styles with an instrument assessing the leader’s least preferred co-worker (LPC); that is, the attitude toward the follower the leader liked the least. This was considered an indication more generally of leaders’ attitudes toward people. If a leader can single out the person she likes the least, but her attitude is not all that negative, she would receive a high score on the LPC scale. Leaders with more negative attitudes toward others would receive low LPC scores.

Based on the LPC score, Fiedler considered two leadership styles. Task-motivated leadership places primary emphasis on completing the task and is more likely exhibited by leaders with low LPC scores. Relationship-motivated leadership emphasizes maintaining good interpersonal relationships and is more likely from high-LPC leaders. These leadership styles correspond to task performance and group maintenance leader behaviors, respectively.

As organizations become flatter (that is, fewer hierarchical levels) and more globally and technologically interconnected, old leadership theories will become outdated. Although the three elements of leadership—the leader, the followers, and the situation—will still be part of the whole leadership equation, how these three elements interact to successfully accomplish a team’s mission and goals are changing. Successful leaders in tomorrow’s workplaces will need to be more like chameleons, adapting to complex and dynamic environments. Discussion Question 1: Why are old leadership theories becoming outdated? Discussion Question 2: “Without people, leaders are nothing”. What does this mean? |

--------------------------------------------------

Multiple-linkage Model

The multiple-linkage model (Yukl, 1981, 1989) was developed after the other early contingency theories, and it includes ideas from some of those theories. However, the broadly defined leadership behaviors in most earlier theories were replaced by more specific types of behaviors. Other unique features include a larger number of mediating and situational variables, and a more explicit description of group-level processes. The explanation of how these variables are relevant includes ideas from the literature on motivation, organization theory, and team leadership. The multiple-linkage model describes how managerial behavior and situational variables jointly influence the performance of individual subordinates and the leader’s work unit. The four types of variables in the model include managerial behaviors, mediating variables, criterion variables, and situational variables.

Mediating Variables

The mediating variables are defined primarily at the group level, like theories of team leadership:

- Task commitment: members strive to attain a high level of performance and show a high degree of personal commitment to unit task objectives.

- Ability and role clarity: members understand their individual job responsibilities, know what to do, and have the skills to do it.

- Organization of the work: effective performance strategies are used and the work is organized to ensure efficient utilization of personnel, equipment, and facilities.

- Cooperation and mutual trust: members trust each other, share information and ideas, help each other, and identify with the work unit.

- Resources and support: the group has budgetary funds, tools, equipment, supplies, personnel, facilities, information, and assistance needed to do the work.

- External coordination: the activities of the group are synchronized with the interdependent activities in other subunits and organizations (e.g., suppliers, clients).

Situational Variables

Situational variables directly influence mediating variables and can make them either more or less favorable. Situational variables also determine the relative importance of the mediating variables as a determinant of group performance. Mediating variables that are both important and deficient should get top priority for corrective action by a leader. Conditions that make a mediating variable more favorable are similar to “substitutes” for leadership. In a very favorable situation, some of the mediating variables may already be at their maximum short-term level, making the job of the leader much easier. Situational variables affecting each mediating variable are briefly described in this section.

Situational variables that can influence task commitment include the formal reward system and the intrinsically motivating properties of the work itself. Subordinate task commitment is more important for complex tasks that require high effort and initiative and have a high cost for any errors. Member commitment to perform the task effectively will be greater if the organization has a reward system that provides attractive rewards contingent on performance, as in the case of many sales jobs. Intrinsic motivation is likely to be higher for subordinates if the work requires varied skills, is interesting and challenging, and provides automatic feedback about performance.

Short-Term Actions to Correct Deficiencies

A basic proposition of the theory is that leader actions to correct any deficiencies in the mediating variables will improve group performance. A leader who fails to recognize opportunities to correct deficiencies in key mediating variables, who recognizes the opportunities but fails to act, or who acts but is not skilled will be less than optimally effective. An ineffective leader may make things worse by acting in ways that increase rather than decrease the deficiency in one or more mediating variables. For example, a leader who is very manipulative and coercive may reduce subordinate effort rather than increasing it.

Types of Specific Actions for Improving Weak Performance Determinants Low subordinate task commitment or confidence

Low subordinate task knowledge and skills

Low coordination and inefficient procedures for the work

Inadequate resources to do the work

Weak external coordination

|

Long-Term Effects on Group Performance

Over a longer period of time, leaders can make larger improvements in group performance by modifying the situation to make it more favorable. Effective leaders act to reduce constraints, increase substitutes, and reduce the importance of mediating variables that are not amenable to improvement. These effects usually involve sequences of related behaviors carried out over a long time period. More research has been conducted on short-term behaviors by leaders than on the long-term behaviors to improve the situation. Useful insights are provided by literature on leading change, making strategic decisions, and representing the team or work unit.

- Gain more access to resources needed for the work by cultivating better relationships with suppliers, finding alternative sources, and reducing dependence on unreliable sources.

- Gain more control over the demand for the unit’s products and services by finding new customers, opening new markets, advertising more, and modifying the products or services to be more acceptable to clients and customers.

- Initiate new, more profitable activities for the work unit that will make better use of personnel, equipment, and facilities.

- Initiate long-term improvement programs to upgrade equipment, and facilities in the work unit (e.g., replace old equipment, implement new technology).

- Improve selection procedures to increase the level of employee skills and commitment.

- Modify the formal structure of the work unit to solve chronic problems and reduce demands on the leader for short-term problem-solving.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Guidelines for Adaptive Leadership

In order to be effective, leaders need to adapt their behavior to changing situations. The following guidelines can help leaders be more flexible and adaptive to their situation. The guidelines are based on findings in research on contingency theories and other research using descriptive methods.

- Understand your leadership situation and try to make it more favorable.

- Learn how to use a wide range of relevant behaviors.

- Identify effective behaviors for your objectives and situation.

- Use more planning for a long, complex task.

- Provide more direction to people with interdependent roles.

- Monitor a critical task or unreliable person more closely.

- Provide more instruction and coaching to an inexperienced subordinate.

- Be more supportive of someone with a highly stressful task.

Guidelines for Managing Immediate Crises

One type of leadership situation that is especially challenging is an immediate crisis or disruption that endangers the safety of people or the success of an activity. Examples of this type of crisis include pandemic, serious accidents, explosions, natural disasters, equipment breakdowns, product defects, sabotage of products or facilities, supply shortages, health emergencies, employee strikes, sabotage, a terrorist attack, or a financial crisis.

- Anticipate problems and prepare for them.

- Learn to recognize early warning signs for an impending problem.

- Quickly identify the nature and scope of the problem.

- Direct the response by the unit or team in a confident and decisive way.

- Keep people informed about a major problem and what is being done to resolve it.

- Use a crisis as an opportunity to make necessary changes.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.